In a situation where everyone has to say the same thing about a country, topic, or person, it is necessary to sneer and lie. Especially if this country is accused of backwardness and bigotry, especially by the West, this pursuit gains legitimacy. Afghanistan, which the world only looks at from afar and learns from movies or news, is an example of such a scenario-country. There, which is an expression of distance, every single image of what is going on is inevitably fictional. All the messages that this fiction tried to give to the world, especially after 9/11, tried to justify the reasons for invading this ancient country.

Today, the new Taliban era also marks a period in which Western cameras are watching what is happening, just like a soldier with his hand on the trigger of a gun, and will use the slightest weakness as a new scenario. Every stalemate and chaos that a post-American Afghanistan will fall into for Westerners will perhaps be shown in new films as the full drama of an Afghanistan without the US. Meanwhile, the Taliban will continue to be portrayed as “incorrigibly ignorant”, “brutal oppressors” and “vulgar Muslims” as previously propagated. Indeed, Afghanistan, with its dark image on the screen, is described as a prison where innocent women are locked into the evil world of religious and, therefore, primitive men.

Cinematic narratives: Between clichés and facts

Every cliché, of course, has a side that touches the truth. However, cinematic clichés corrupt reality by over-repetition. The viewers are stunned by the nature of the images appearing here, which do not leave a gap in the world of thought, especially if the audience does not have prior knowledge about the person, subject or countries mentioned. In that case, the cinematic perspective will offer him an easy formula of what he should think about these people, subjects and countries. Afghanistan is a dangerous and distant geography as in the narratives. This distance does not refer to a purely spatial distance. It is more about the imaginary and intellectual possibility. Man is close to where he can dream and think. Despite globalization, Afghanistan is getting further and further away from the world with each passing day.

Afghanistan is close to death and far from life. In the words of Khaled Hosseini, author of The Kite Runner, “goodness has left this land; There is no way to escape death. Death is death everywhere, anytime.” Where there is no life, people can only exist with their bodies. They cannot feel life with its beauties and blessings, and they cannot taste its delights. The sun rising for them is not enough to illuminate their home. Wandering its occupied streets does not fill their hearts with the feeling of freedom. The bazaars and markets they wander around without knowing it, while passing from right to left from bombs that may explode suddenly, do not offer them an escape opportunity. In every country, where occupation reigns, such as Afghanistan, deaths catch people suddenly. Such a death does not only affect women and children, but it encompasses all people and all humanity.

Despite this, death is presented as something in which only men are portrayed as subjects in Afghan narratives. However, evil finds and strikes everyone. This is the nature of evil. But in propaganda culture, evil is not only portrayed badly: it also includes those who portray it more badly. They take evil from one person or country and spread it all over the world. This does not mean that the country described is perfect. Every administration on the globe has a critical application in many respects. However, the cinematic view is not simply analytical and critical. It is the magnifier and bender of events, because the truth passes through the ideological filter of the director until it is reflected from the camera lens to the big screen. The artist seeks what he wants to find there more. Even if the director cannot find it, he/she makes it exist by producing it.

Dark reflections

The silver screen begins to darken when movie images fall on it. These images sometimes illuminate, sometimes they mislead by doing so. Interestingly, the movie Kandahar or The Sun Behind the Moon (2001), made just before 9/11, deals with Taliban-led Afghanistan. Directed by Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, the film tells the story of Nafas, who returns to find her sister who stayed in Afghanistan while fleeing. Nafas’ brother tells her that she will commit suicide in the last solar eclipse of the millennium. Nafas, who falls on the difficult and threatening roads of Afghanistan, positions herself as a witness of the Taliban experience throughout the film. What she sees and experiences are presented as a naked reflection of the truth in the public opinion of the world. However, this is a distorted and dark reflection.

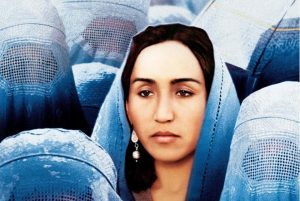

Kandahar, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, gained symbolic importance after the events of September 11. If an American had shot this movie, it would have been clear that 9/11 was an excuse or a fiction on the way to the invasion of Afghanistan. Even so, the film was seen worthy of the Federico Fellini Award given by UNESCO. Of course, the political side of such festivals and awards should not be ignored. Part of the shooting of the documentary, which resembles a documentary, was completed in Iran and partly in Afghanistan. The only thing that is told and repeated throughout the movie is to show that Afghanistan, and the Taliban, is the reason why the people of Afghanistan are miserable and enslaved. For this purpose, burqas as symbols of captivity and images of helpless women in burqas are emphasized.

According to this view, covering up, or wearing a hijab, cannot be a choice because the measure of freedom in modern culture is the display. These women are women to the extent that they emulate make-up. In this sense, the film literally addresses the demands and expectations of the Western eye. However, every act of showing is also an attempt to hide. The reality that a director close to the region, who is to some extent an insider, like Makhmalbaf ignores and hides these aspects is the real problem of Afghanistan. For example, nowhere in the movie is the question asked about why the people of the country are so poor. What the community that makes up the Taliban really is and what circumstances motivate them are also not questioned. The director addresses only interesting problems. On this point of interest, there is nothing better than the story of an unfree woman in the Islamic world or a girl who cannot get an education.

Examples of other clichés

At Five in the Afternoon (2003), directed by Samira Makhmalbaf, Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s sister, explores the same female problematic, albeit with a partially optimistic approach. According to the story, Noqreh, who lives in the post-Taliban era, is religious and bigoted according to the language of the film, and is determined to rule the country by overcoming the narrow world directed by her father. For this reason, she often avoids Quran courses and tries to get a secular education. Inspired by the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto, artists and poets support her. The bigots are on the other side; they are always the other and virtue is at the other end! At the end of the movie, her father decides to migrate deep into the desert, where he assumes no blasphemy. Of course, Noqreh forcibly joins her father with his unfulfilled dreams. This is a drama that will justify the intervention of the Western hand. However, there are many girls and boys in the West who are deprived of their dreams by being exploited or pushed out of the race by the competitive capitalist culture in which they live, even though such a film has not been made. The animated movie The Breadwinner or Parvana (2017), produced by M. Polk Gitlin and Angeline Jolie, and directed by Nora Twomey, tells the struggle-filled story of an 11-year-old girl named Parvana, who was crushed under the “oppressive” rules of the Taliban. The film, which had its world premiere at the Toronto Film Festival, was nominated for the best animation at the 90th Academy Awards. Parvana, whose father is imprisoned, has to work to earn money. However, it is impossible for a girl to study or work in Afghanistan. For this, she tries to survive and save her father by cutting her hair and dressing like a man, just like in the movie Osama.

In the movie Osama (2003), directed by Siddiq Barmak, the protagonist Osama is portrayed as a girl trying to stay clean in the ugly world of the Taliban. The film, which was entirely shot in Afghanistan, was supported by many international production companies. Parvana resembles the 2007 animated movie Persepolis. Persepolis claims to describe the “closed” world of Iran after the Islamic Revolution through the eyes of the French. There, too, the depressive events and the vengeance of the black sheet itself are recounted on 9-year-old Marjane. In all these films, Islam is always portrayed as the theoretical background of radical actions. Meanwhile, Persepolis won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes. Although it falls into similar stereotypes among movies on Afghanistan, the relatively mild one is The Kite Runner, directed by Marc Forster, who treated the image of the Taliban like other films. Ultimately, the film is about the desperate situation in Afghanistan that not only evokes a solution as inevitable, but also puts fleeing the country as such. However, the land of childhood, the capital of human memory, can never be forgotten, even if one travels far from it.

Not forgetting certain things:

As Afghan-born Khaled Hosseini says in The Kite Runner, “when you kill a person, you steal a life.” Yet what is stolen in Afghanistan is not just human life, but a country itself with everything that lives in it: its people, its values, its history, its traditions, its culture, its art… This is one of the distinguishing features of the Western occupation. Where it goes not only consumes the land, but leaves it as a black dot on the map of the global psyche. So much so that even the people of the country are shown as the cause of the fall of their country. Evil seems to always come from within, not from the outside. There is a country itself and the perception of the country on people. These two do not always mean the same thing. Sometimes they can even be opposites. Of course, Afghanistan is not entirely unrelated to all the smears about itself. Here, crimes that compelled the conscience and exceeded the limits were committed. Today’s Taliban have to face these mistakes in their past and learn lessons. However, this reckoning is valid for all countries of the world. Moreover, it would not be a consistent and honorable view not to impose any burdens and obligations on the United States and some of its allies, who rightfully waited for Afghanistan to self-criticize and dyed the whole region with blood after 9/11.

The truth is that blood stains do not come off easily. It will not be enough to apologize for the civilians killed in the airstrike on 29 August 2021, and only God knows the number of similar attacks conducted. Unfortunately, every pain that hits will be a reason for new pains, because every pain born from its own ashes turns into the cause of new destruction in an endless vicious circle. All these tragedies, which are tried to be covered up on the big screen of cinema, will only be enough to convince a certain number of people for a certain period of time. This article can be concluded with the dialogue between Emir’s father, who is preparing to flee Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion, and his friend Rahim Khan in the movie The Kite Runner. As a matter of fact, this dialogue is a clear summary of today’s Afghanistan after the US.

Emir’s father: Will you keep an eye on the house for me? We’ll be back when the Russians are gone.

Rahim Khan: What if they do not go?

Emir’s father: Everyone goes. This country is not kind to invaders!