The horrific images of Russia’s devastating war flood our screens. Meanwhile, the Russian propaganda machine is running at full speed, though this time less successfully in the West compared to its war in Syria. Anyone who has been paying attention to the situation in Syria closely will recognize Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a déjà vu.

Back to 2015

In the spring of 2015, the Free Syrian Army was advancing in Syria and controlled about 60 percent of the country by June 2015, despite the lack of modern weapons. Russia intervened vigorously. Putin saved the Assad regime with a ruthless aerial bombing campaign. The opposition area dwindled city by city, village by village and now mainly consists of a small strip north of Aleppo and Idlib, where Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) has now largely taken over from the weakened opposition by a coup. This military campaign by the regime and Russia is still going on, on the fringes of this area, with minimal coverage in Western media. Russia, pretending to tackle terrorism, bombed almost only in the West of the country, while ISIS was actually in the East. Hospitals, residential areas, markets, and refugee convoys were targeted by Russian ‘counter-terrorism’. Towns and villages were wiped out, and the population fled. “As a result, there are still some 2.8 million displaced people in Northwestern Syria,” Omar Safadi told me in Gaziantep. He is a spokesperson for the Independent Doctors Association (IDA). They run several hospitals and clinics in camps and towns in Northwest Syria.

Besides, Russia has killed more civilians in Syria than ISIS.

“The refugees feel safe there, because they think Russia won’t dare to bomb on the border with NATO country Turkey,” IDA doctors had told me in the past. When I was in Syria in March 2021, a Russian ballistic missile landed near the Atme camp.

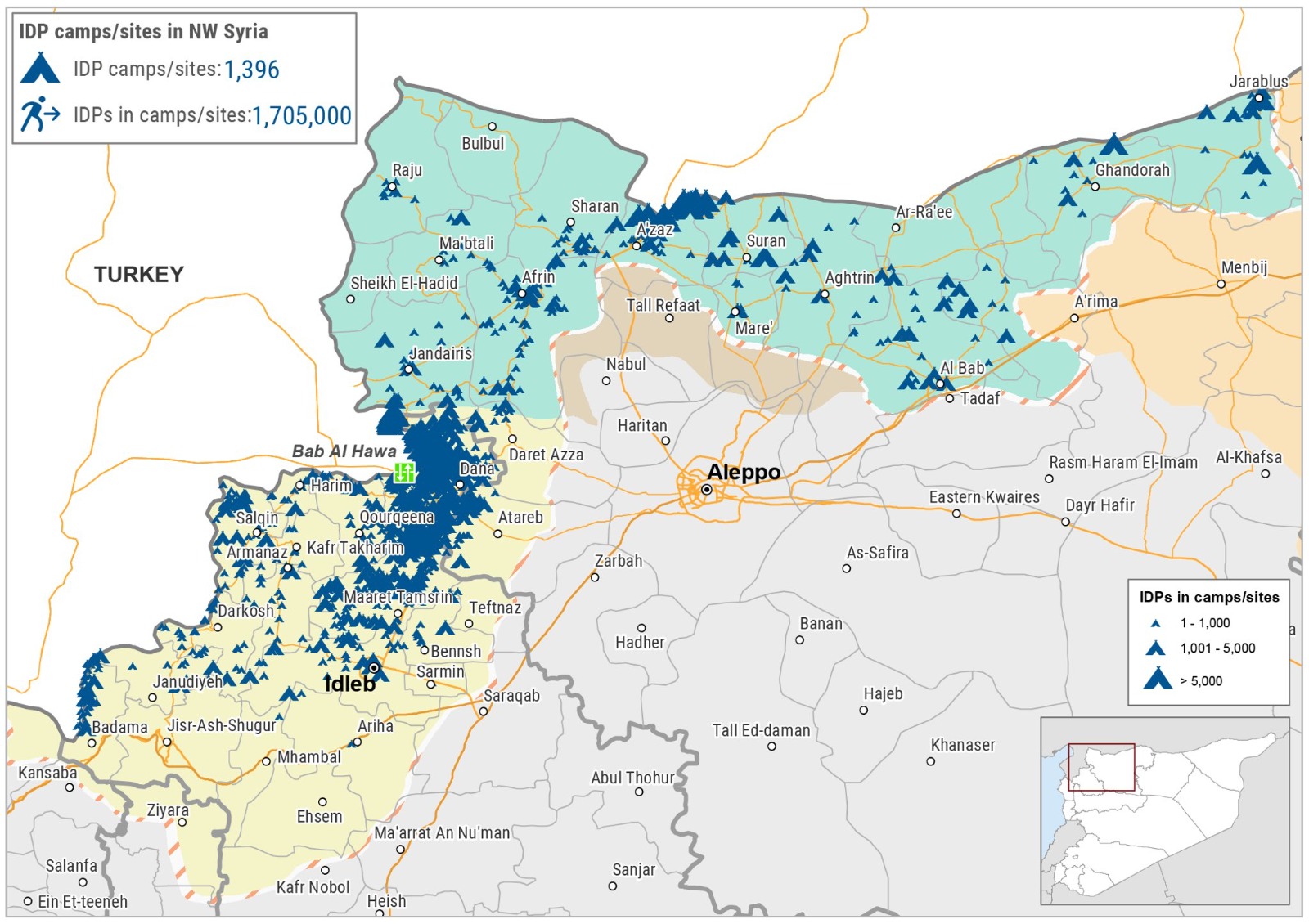

People from the 1,396 camps and makeshift sites, to which they had fled for the military campaign against their towns and villages, and after having endured blizzards and floods in often outdated tents – sometimes even for years on end – now face a new sword of Damocles. These most vulnerable displaced people rely on outside humanitarian assistance for tents, food, medicine and education. Traveling around the area, you see tents everywhere.

Russia could block the extension of the UN cross-border operation via the Bab al-Hawa border crossing from Turkey. Russia, together with China, previously blocked three other border crossings for UN humanitarian assistance to areas beyond the control of the Assad regime.

In 2014, the permission in the UN was for two years, and it was then extended. After a while, it was reduced to one year. The four border crossings were Bab al-Hawa to Idlib, Bab al-Salama to northern Aleppo, Ya’roubiya to northeast Syria and one from Jordan. In 2018, it was narrowed down to just the first two border crossings and later to just one. UN agencies can therefore only operate from Gaziantep.

Last June, Russia threatened to close the last border crossing. US President Biden negotiated with Putin and managed to avert the disaster. Russia’s war against Ukraine has greatly deteriorated Russia’s relations with the West, and the repetition of such a solution for this year seems impossible.

Some 4.2 million Syrians reside in the two areas combined, most of them displaced from all parts of the country. The residents themselves call it Little Syria. Of these people, 1.7 million live in 1,396 camps or makeshift sites without facilities in Northwestern Syria, according to the UN’s Mark Cutts. “Most of the displaced are on the Idlib side. In early 2020 alone, over 1 million people were displaced. Across the Northwest, this is 70 percent of the population,” said Safadi.

Not all of them live in camps, some live in rental housing, collective centers, or in public buildings. Residents who lived in or moved from the area prior to 2011 make up approximately 30 to 40 percent of the population. In addition, 60 to 70 percent of the population have fled from other parts of Syria. Everyone who escaped the regime has come to this area.

According to the Independent Doctors Association, 2.1 million of the 2.8 million displaced people depend on cross-border aid, which includes education, tents, and medicine. Will people flee to Turkey? Safadi said: “No, people will not flee to Turkey, people will die in tents. Most displaced people have no income. The UN is 40 to 50 percent responsible for Syria’s humanitarian response.”

“Look at what happened in besieged Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. The regime’s food chain to besieged territory lasted for two months, but all food aid arrived damaged or past its expiration date. I think Russia is using the veto, the cross-border resolution, and pushing the UN to operate out of Damascus, by-passing US and EU sanctions through the backdoor. And that Russia wants to revive the Syrian regime and use the humanitarian funds for that,” said Safadi.

“Northern Syria is only accessible through Turkey. There are no helplines from Damascus or any other area. There is no official report that I am aware of, but I believe humanitarian organizations cover at least 70% of basic living expenses. The vulnerability of the people throughout Northwestern Syria is the same. Somehow it doesn’t affect us much as a humanitarian organization, we react the same in both areas,” explains Safadi.

“The UN’s framework on aid in Syria is as if the regime is fully legitimate,” says political advisor Malik al-Abdeh. “Honest human conflict and human rights analyses are absent. To give you an example from the Framework: “As a final reference to the context, Syria has ratified most international human rights instruments, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which, alongside the recommendations emanating from the human rights mechanisms, constitute the basis for the UN human rights-based approach to programming in the country.”

Moreover, al-Abdeh says, “Turkey has suspended export of wheat to Northern Syria, fearing these commodities will run low in Turkey itself because of the Ukraine war. This will make Northern Syria more dependent on aid than ever before”. “According to a UN OCHA source in Gaziantep, most of the aid that the UN distributes to regime areas is sourced in Turkey. It doesn’t make sense to send aid to Damascus and then deliver it across the border line to Northern Syria when the opposite should happen,” he says.

Neither does it make sense that the regime, which used chemical weapons against its own people and dropped thousands of barrel bombs on cities like Aleppo, should be entrusted with delivering aid to the same areas it considers full of “terrorists.”

“I wonder whether Russia’s hostage grip on aid in Syria is coming to an end given the Ukraine war. It’s crazy to rely on Putin’s goodwill given where we are now. There needs to be a push for planning for continued cross-border aid delivery in the absence of a UN mandate. The UN is dysfunctional right now; and will probably be quiet for some time, and the world needs to move on that basis,” he says.

I think this is the core message: Russia’s hostage taking on aid needs to be broken. The West can do that if they work with Turkey on cross-border deliveries without a UN mandate.” Russia sucks up so much diplomatic energy and time on this cross-border mandate that the West feels like it achieved something when it is renewed when it really shoudn’t be an issue.